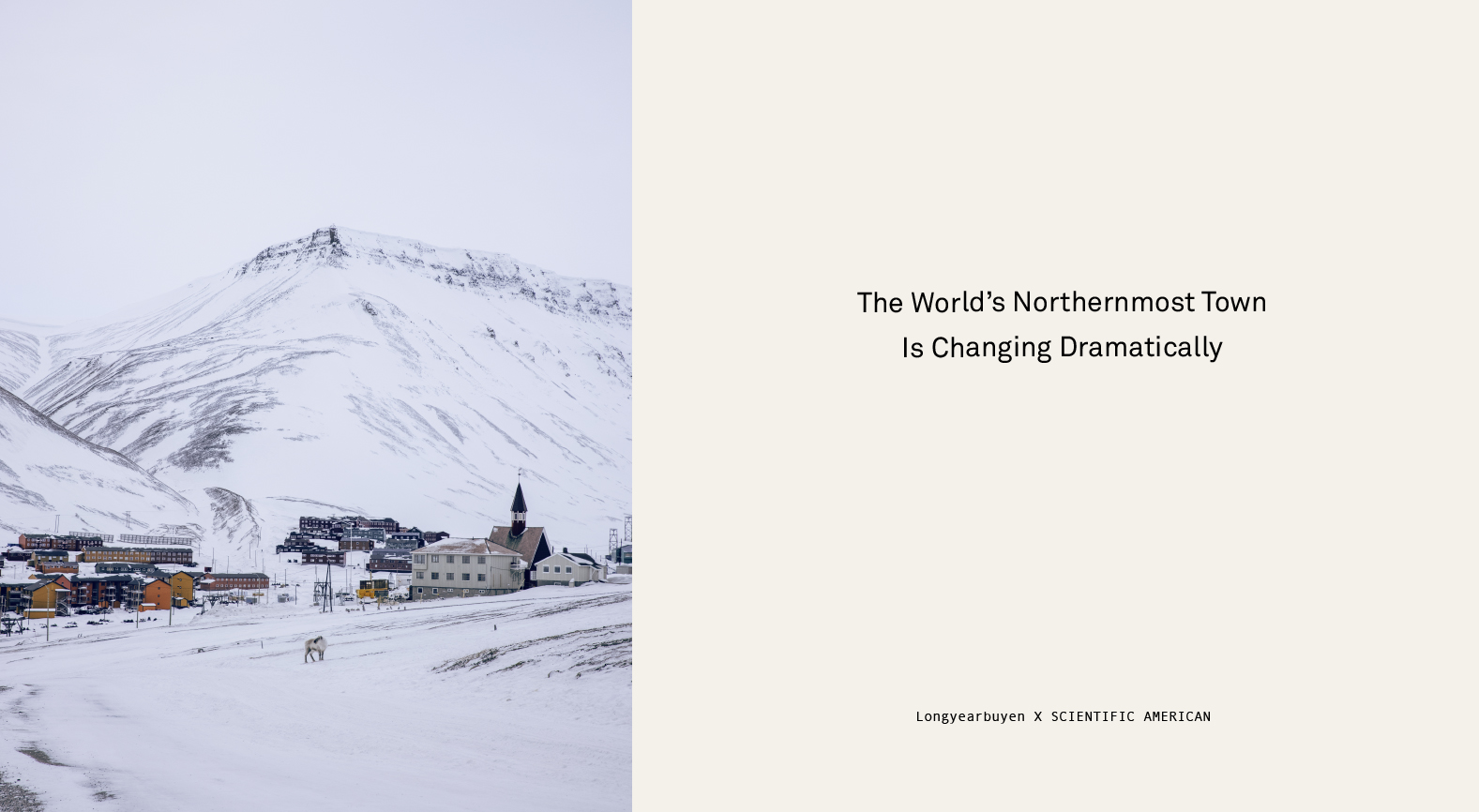

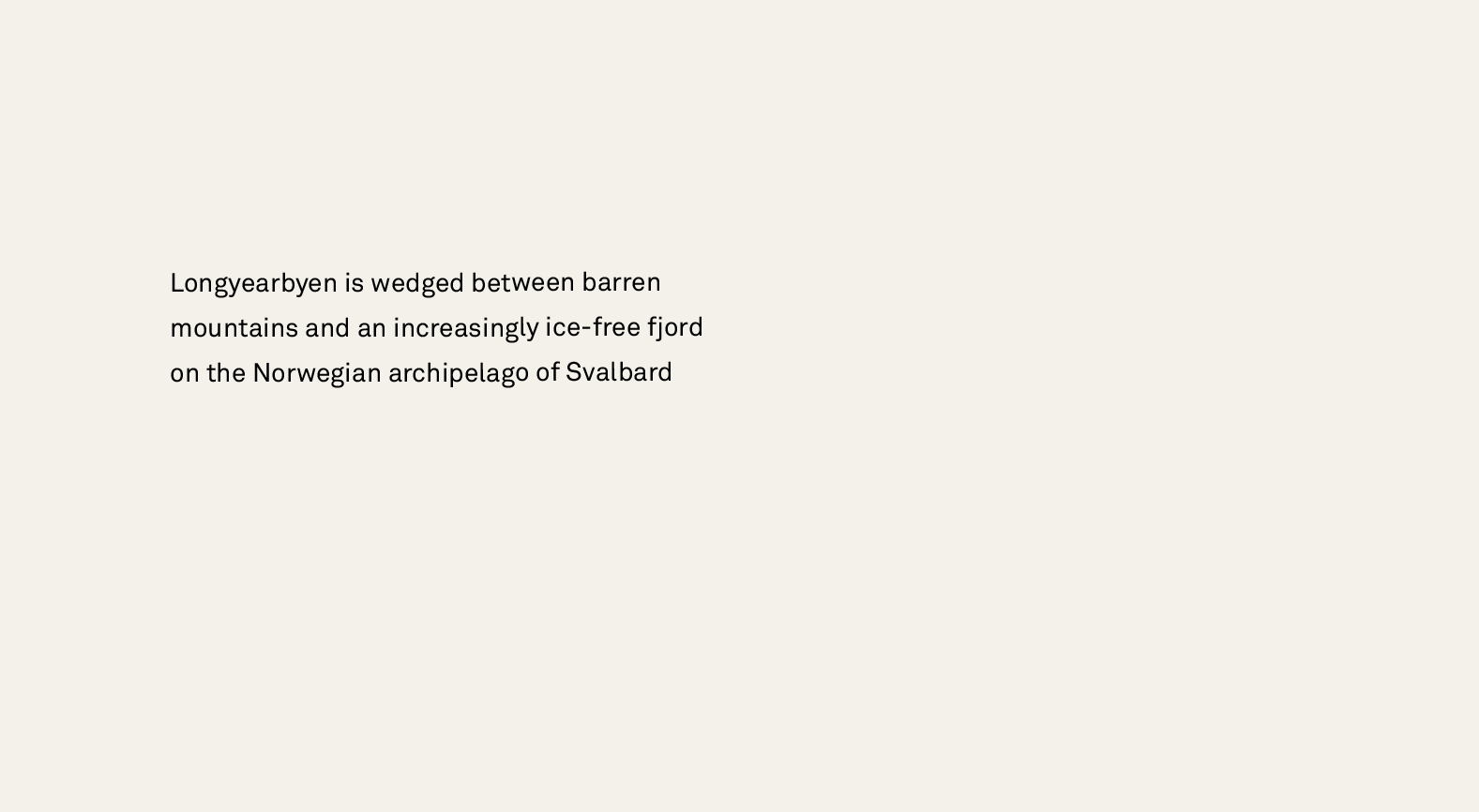

Climate change is bringing tourism and tension to Longyearbyen on the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard.

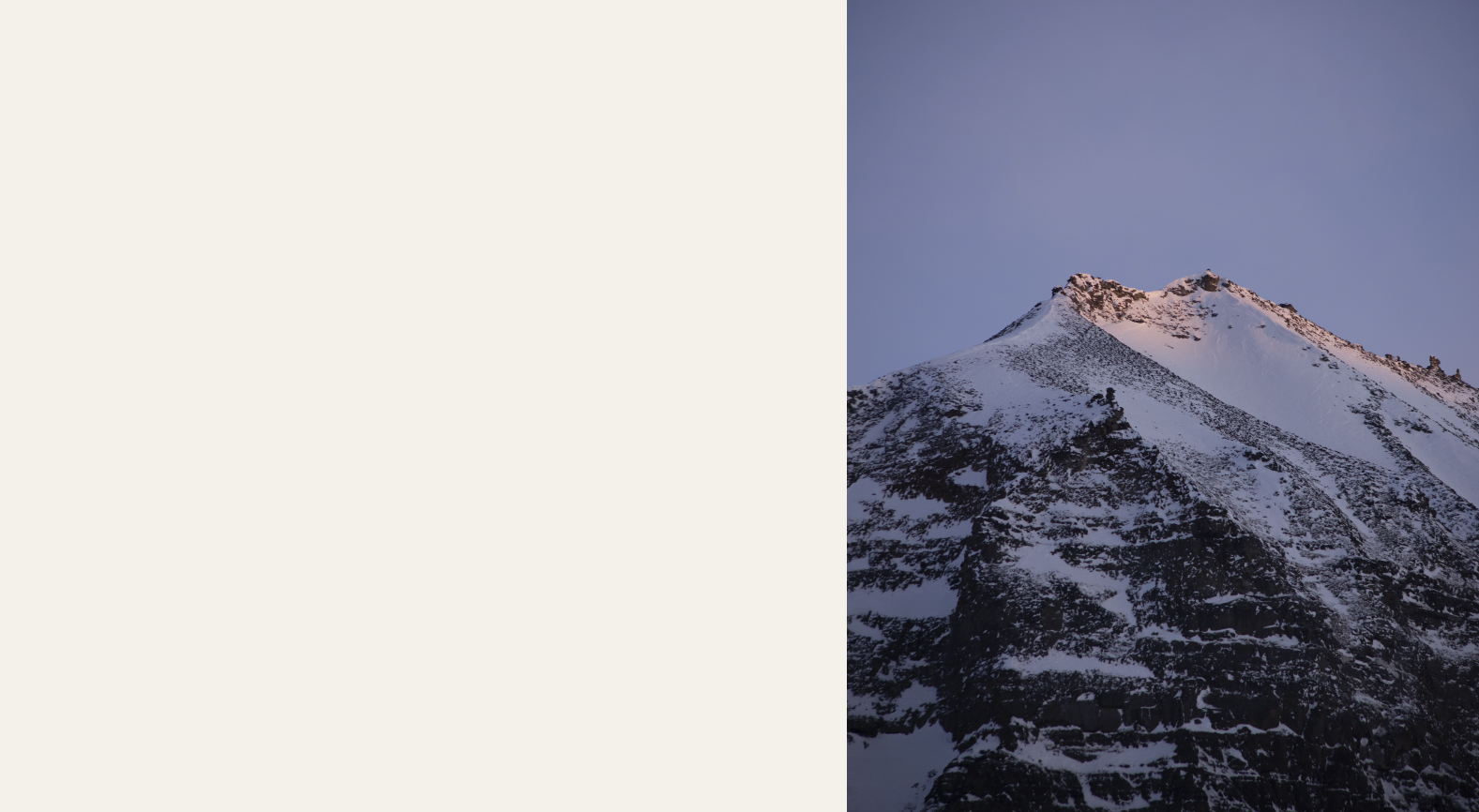

Since 1971 temperatures on Svalbard have risen by roughly four degrees Celsius, five times faster than the global average. In winter it is more than seven degrees C warmer than it was 50 years ago. Last summer Svalbard recorded its hottest temperature ever—21.7 degrees C—following 111 months of above-average heat.

Annual precipitation on Svalbard has increased by 30 to 45 percent over the past 50 years, largely in the form of winter rain, according to the Norwegian Meteorological Institute. And the archipelago's permafrost—ground that should remain largely frozen—is now warmer here than anywhere else at this latitude. Even by Arctic standards, Svalbard is heating up fast.

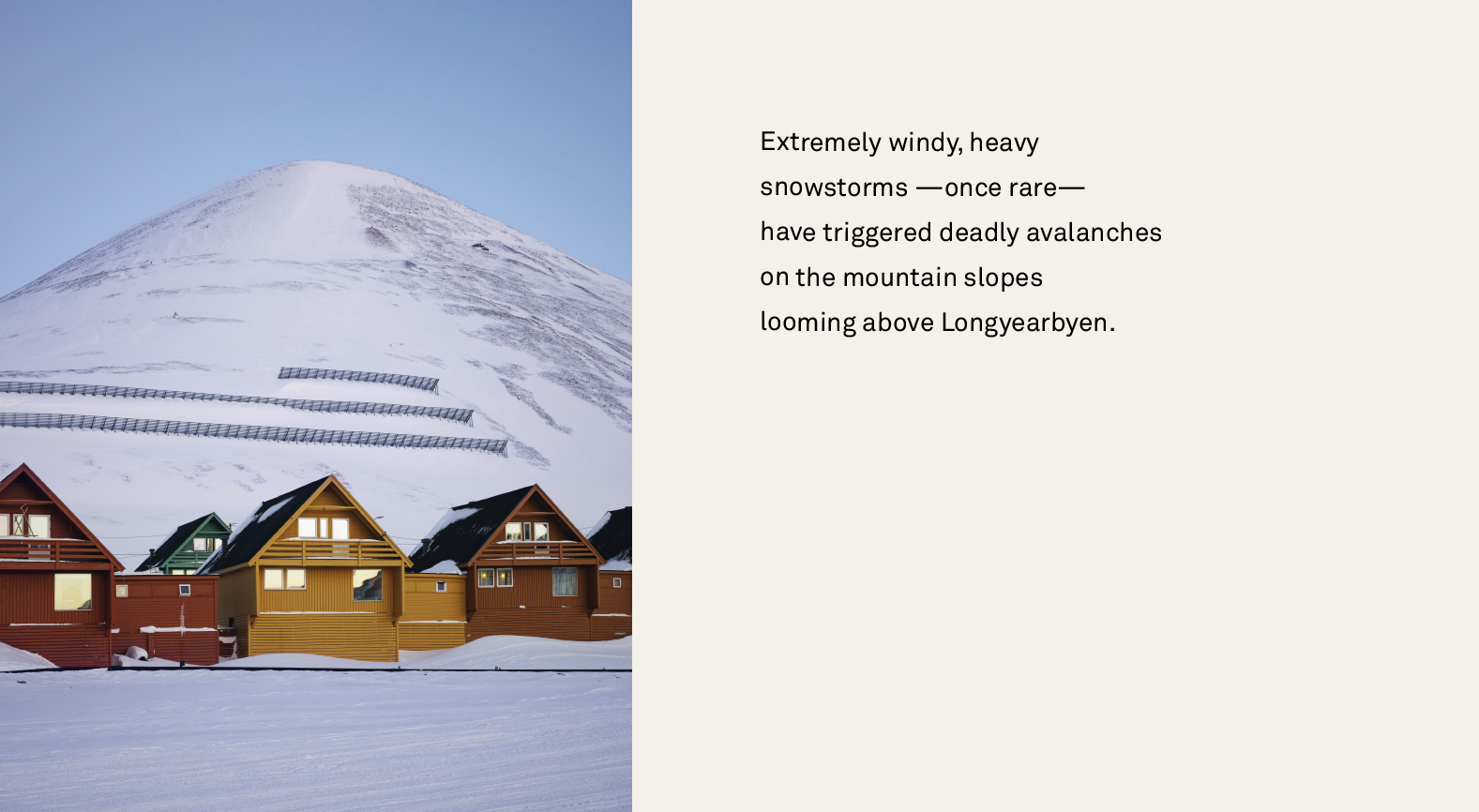

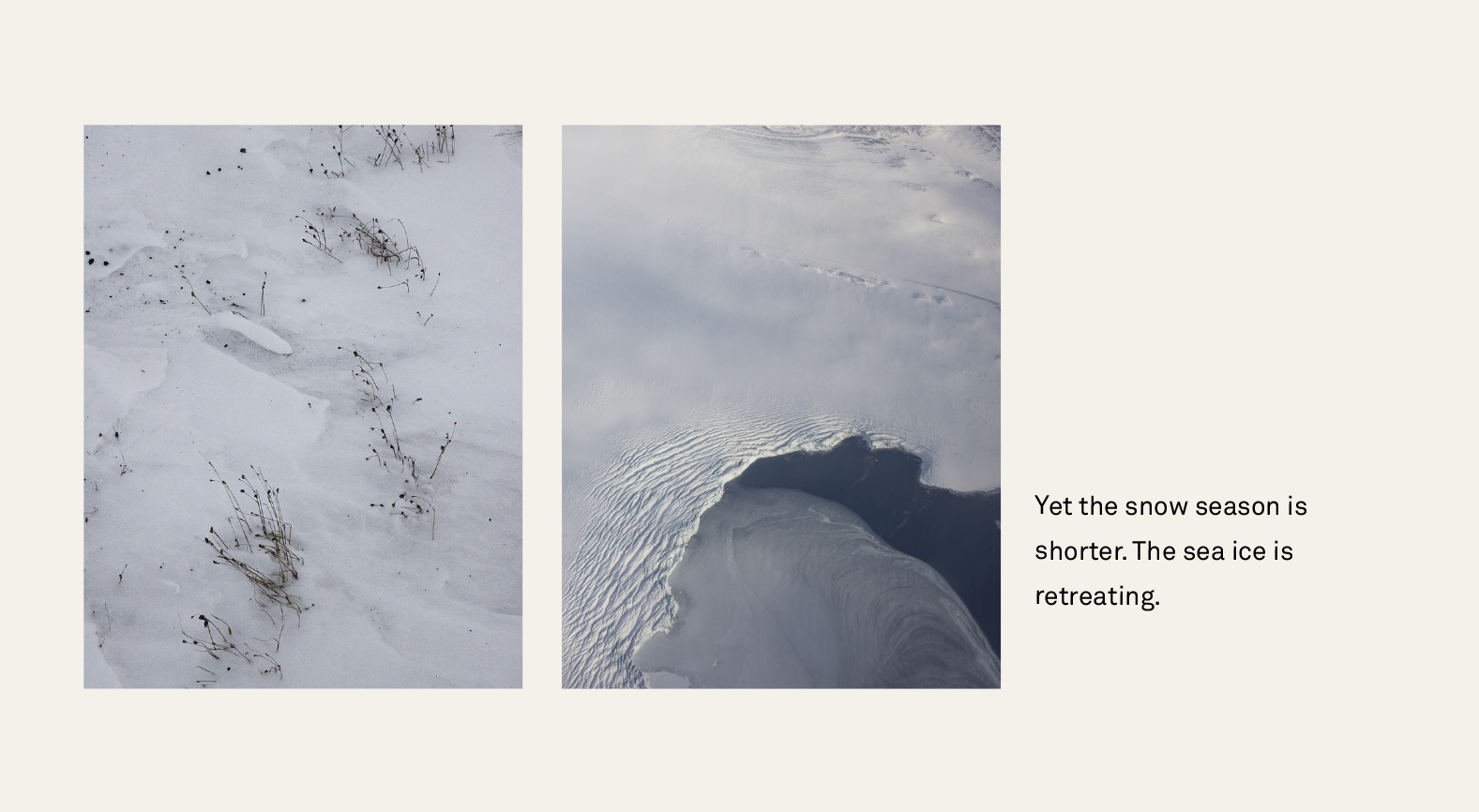

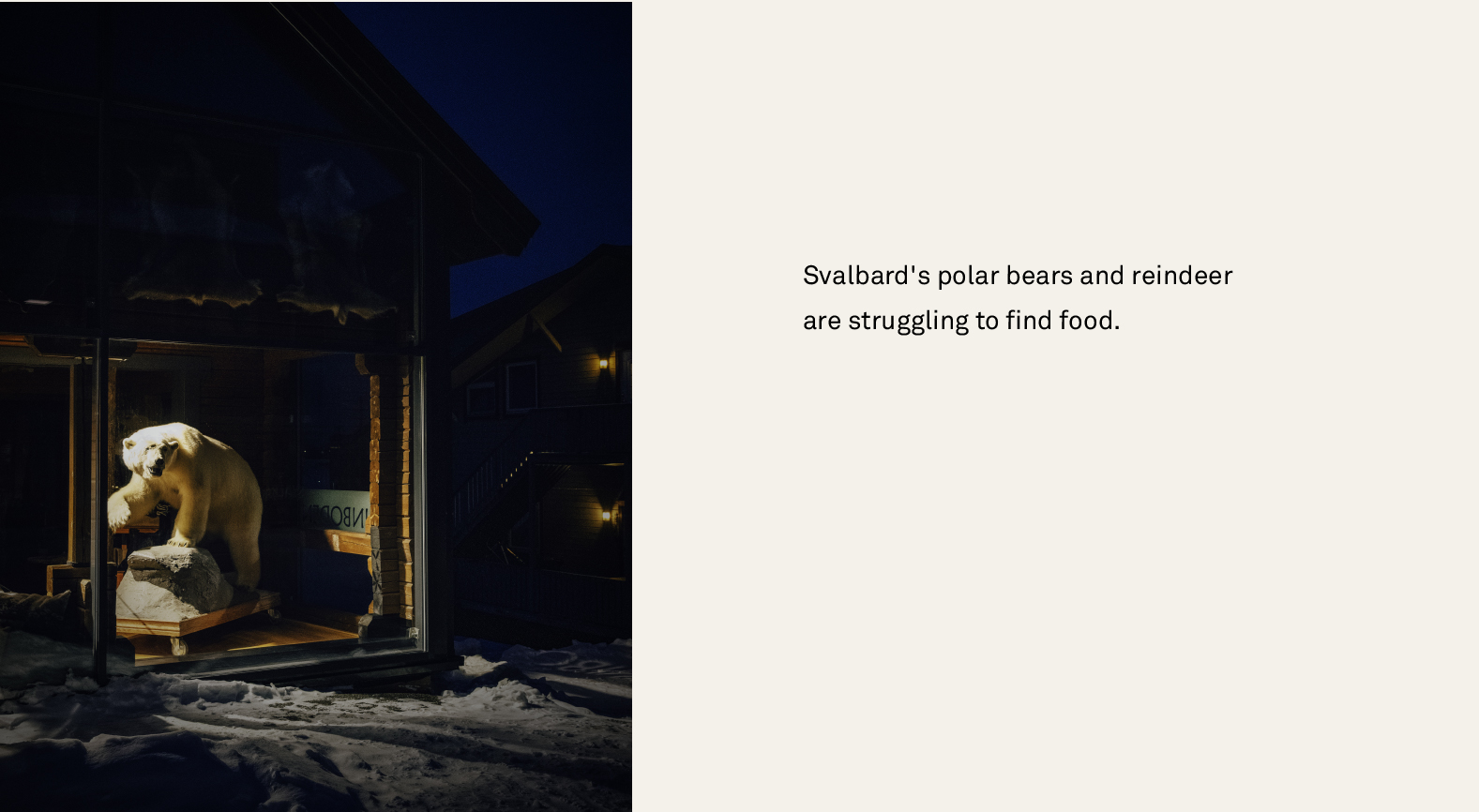

The consequences are extensive. The thawing permafrost, which can heave or slump, has ruptured roads and exposed the macabre contents of old graves. Extremely windy, heavy snowstorms—once rare—have triggered deadly avalanches on the mountain slopes looming above Longyearbyen. Yet the snow season is shorter. The sea ice is retreating. Glaciers that reach down from the mountains are among the most rapidly melting on earth, according to a 2020 Nature Communications study. Svalbard's polar bears and reindeer are struggling to find food.

Scientists expect the land to become less secure. More rain and more meltwater will raise river levels, leading to more flooding and erosion, says Hege Hisdal, director of hydrology at the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate. Since 2009 deep permafrost temperatures have increased at rates between 0.06 and 0.15 degree C per year. When permafrost warms, its active layer—the top layer of soil that thaws during the summer and freezes in autumn—grows deeper. Around Longyearbyen the thaw is deepening by 0.5 to two centimeters annually, and the town's structural instability deepens with it.

Article by By Gloria Dickie for Scientific American